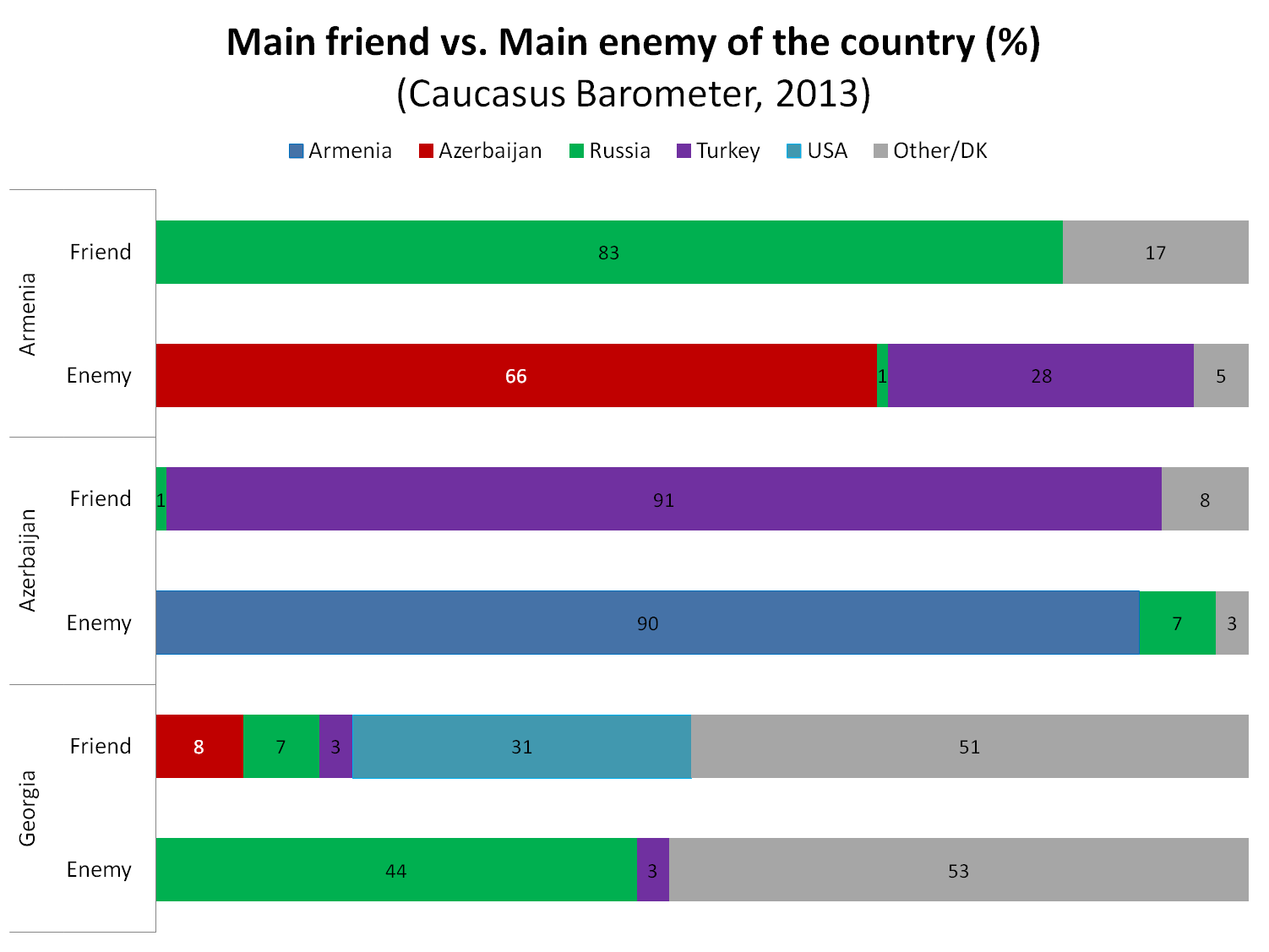

The majority of Armenian respondents to the 2013 Caucasus Barometer (CB) questionnaire named Russia as Armenia’s biggest ally (83%), while just under half of Georgian respondents named Russia as an enemy (44%), and 7% in Azerbaijan noted Russia as the main enemy of their country. A split can be seen in the case of Turkey, as most Azerbaijanis view Turkey as an ally (91%) and just over a quarter of Armenians view Turkey as an enemy of their country (28%).

The tension that characterizes cross-border perceptions in the region makes the borders themselves highly securitized spaces. Far from a free flow of people or goods, cross-border trade and travel is restricted between Georgia and Russia, Armenia and Azerbaijan, and Armenia and Turkey following a series of wars over disputed territories.

Nevertheless, perceptions of borders can ebb and flow throughout history. Administrative boundaries can become state borders, as in the case of the South Caucasus in the early 1990s, and state borders can become as open as administrative ones, such as in the European Union. Similarly, perceptions of neighbors can vary across different issue areas. While opinions and alliances in the South Caucasus are largely polarized, the will (if not the actual ability) to trade and interact on a commercial level yields a slightly less tense picture. Countries with a strong negative perception of other countries can be extremely reluctant to engage economically with that country. However, when positions are less polarized, the approval to do business is much stronger.

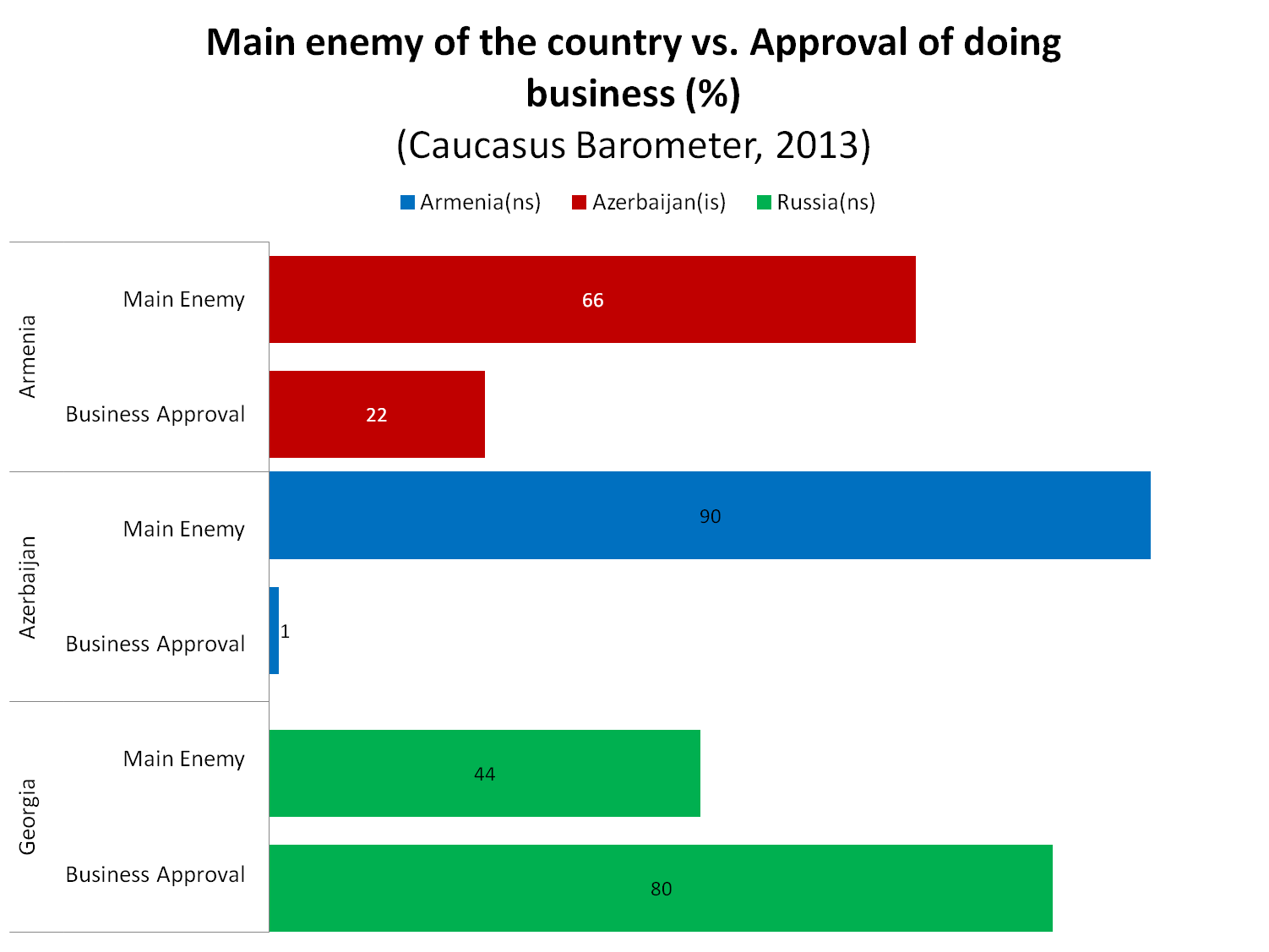

The 2013 CB asked whether people approved of doing business with a range of different ethnicities. The percentage of Armenians, Azerbaijanis and Georgians who approved of doing business with the titular groups of the countries they highlighted as their main enemies is shown below.

In 2013, Azerbaijanis overwhelming felt that Armenia was the main enemy of Azerbaijan, and only 1% said they approve of doing business with Armenians. However, although 66% of Armenians said the main enemy of Armenia was Azerbaijan, a significantly higher amount said they approve of doing business with Azerbaijanis (22%). For Georgians—who have the least polarized views—although 44% said Russia was the main enemy of Georgia, the majority said they approve of doing business with Russians (80%). Economic dependence and economic hardship certainly have a role to play in this pattern, with all three countries naming economic concerns (along with territorial claims) as core problems facing their populations.

However, even though Georgian export dependence on Russia is relatively low at 7%, cross-border trade would almost certainly increase if trade were to become more feasible. While it is not clear from this data whether openness to trade is driving reductions in hostility or vice versa, it is an important reminder that the practical need to coexist has the potential to ease relations between hostile countries. In a region such as the South Caucasus where perceptions of others across borders are so polarized, seeking common ground such as the need for economic development could be a potential arena for cooperation. To explore more aspects of cross-border relations, visit the CRRC’s Online Data Analysis tool.