Note: This article first appeared on the Caucasus Data Blog, a joint effort of CRRC Georgia and OC Media. It was written by Givi Silagadze, a Researcher at CRRC Georgia.The views presented in the article are of the author alone, and do not necessarily reflect the views of NDI, CRRC-Georgia, or any related entity.

While Russia regularly warns against the supposed negative consequences of ‘colour revolutions’, data from the Varieties of Democracy project suggests that anti-regime protests leading to changes of government in former Soviet countries have led to lower corruption, cleaner elections, and more vibrant civil society.

Fearing unrest in their region, Russia’s President Vladimir Putin and the Russian government often refer to the threat of ‘colour revolutions’ dislodging the existing government in neighbouring countries, maintaining that the West is working hard to engineer such a turn of events.

Most recently, Russia’s Foreign Minister Sergey Lavrov, claimed that the 7-9 March protests in Tbilisi were ‘of course being orchestrated from abroad’, and noted that they looked ‘very much like the Kyiv Maidan’.

The outcomes of such protests are clearly implied to be damaging, an idea occasionally explicitly stated: in 2014, Putin, commenting on a popular uprising in Russia, claimed that colour revolutions led to ‘tragic consequences’.

But what do these tragic consequences look like? Data shows that colour revolutions in Armenia (2018), Georgia (2003), and Ukraine (2004, 2014) were associated with reduced corruption, decreased clientelistic relationships between politicians and voters, freer and more vibrant civil society, cleaner elections, and greater freedom.

However, Kyrgyzstan’s Tulip revolution does not appear to have prompted such a clear post-revolutionary improvement on any of these measures.

The Varieties of Democracy (V-Dem) project relies on expert surveys to annually assess 450+ measures of democracy in almost all countries of the world.

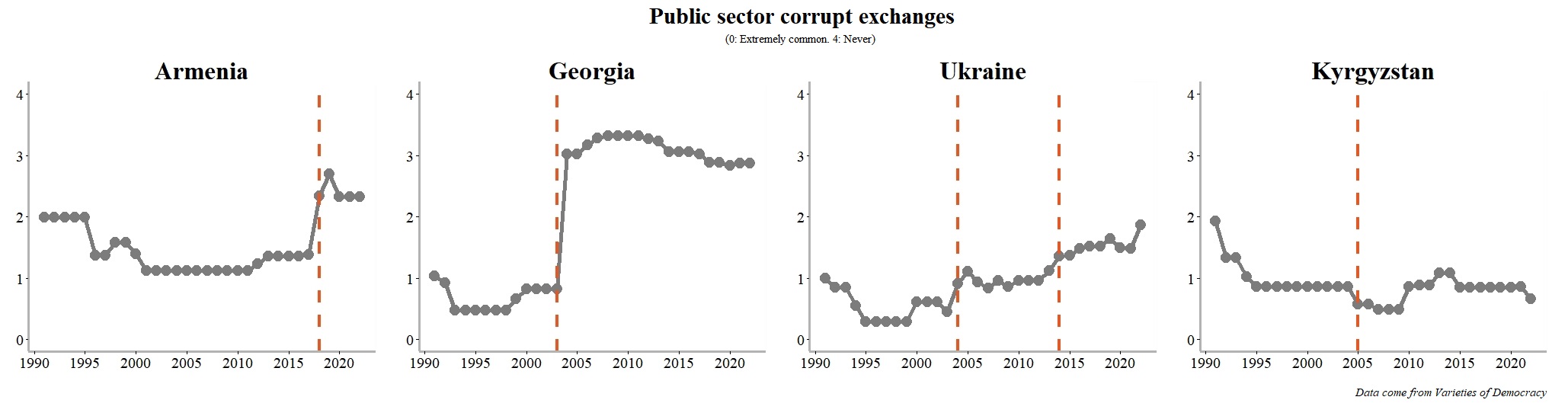

One indicator measures how routinely public sector employees grant favours in exchange for bribes, kickbacks, or other material rewards. In all the selected countries except Kyrgyzstan, the post-revolutionary periods showed decreases in corruption in the public sector. The improvement was the most visible and substantial for Georgia.

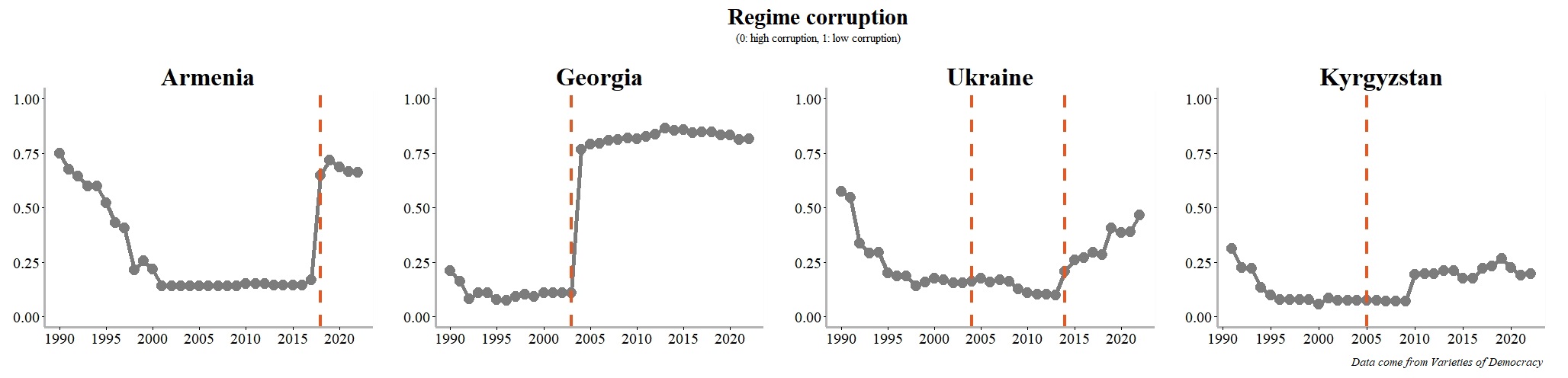

Another measure is of regime corruption, which aims at addressing the question: to what extent do political actors use a political office for private or political gain? On this measure, the picture is similar — revolutions in Armenia, Georgia, and Ukraine were associated with a decline in the magnitude of regime corruption. Exceptions to the pattern were the 2004 Orange Revolution in Ukraine and the 2005 Tulip Revolution in Kyrgyzstan, which did not appear to lead to any changes in regime corruption in the countries.

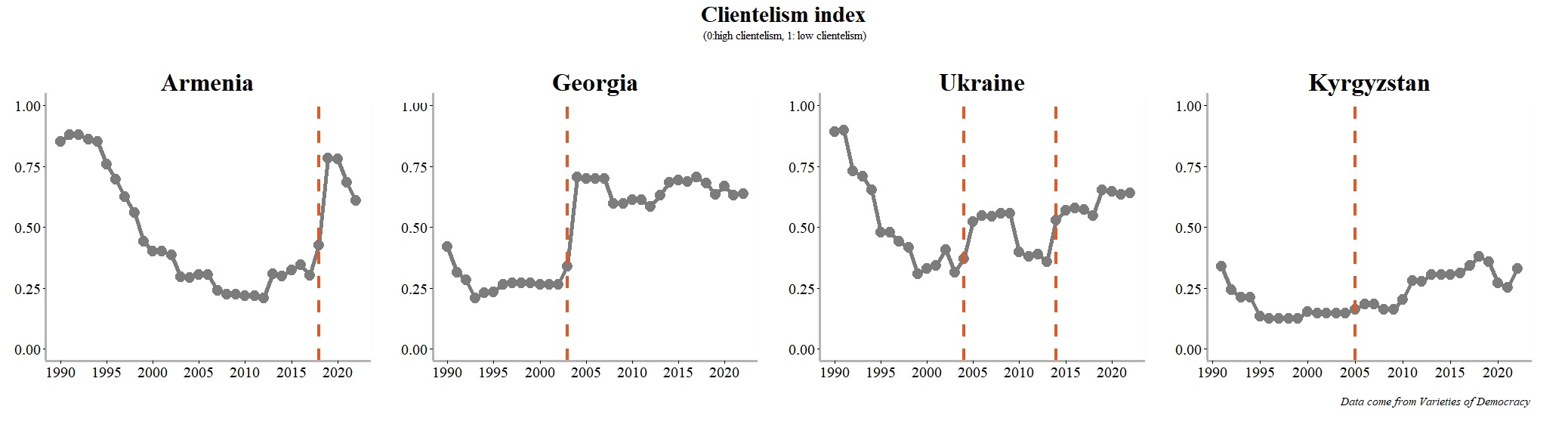

Another indicator of healthy political life is the absence of clientelism. Clientelism refers to a relationship between political actors and voters in which voters’ political support is contingent on targeted rather than public distribution of resources such as jobs, money, and services. The chart below suggests that revolutions in Armenia, Georgia, Ukraine, and Kyrgyzstan were associated with a decline in the extent to which politics was based on clientelistic relationships.

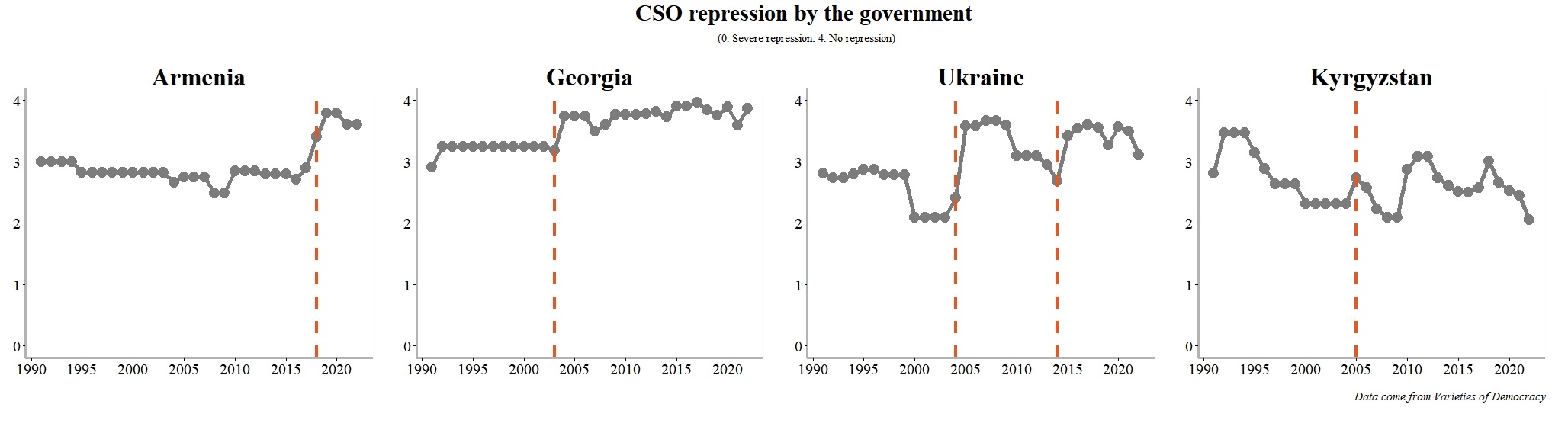

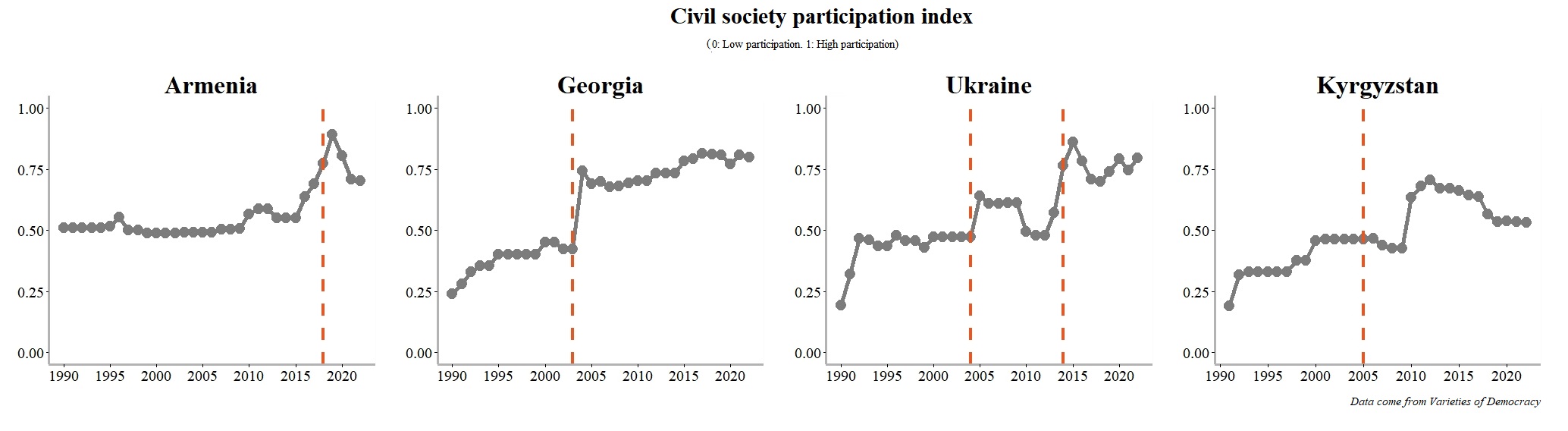

A free and vibrant civil society is a necessary and important component of a well-functioning democracy. The data suggests revolutions led to improved scores, with a decrease in government repression of civil society organisations.

Moreover, the revolutions in Armenia, Georgia, and Ukraine were clearly associated with greater civil society participation, which implies a larger involvement of people in CSOs. As for Kyrgyzstan, it took several years before the country registered improved scores for greater civil society participation.

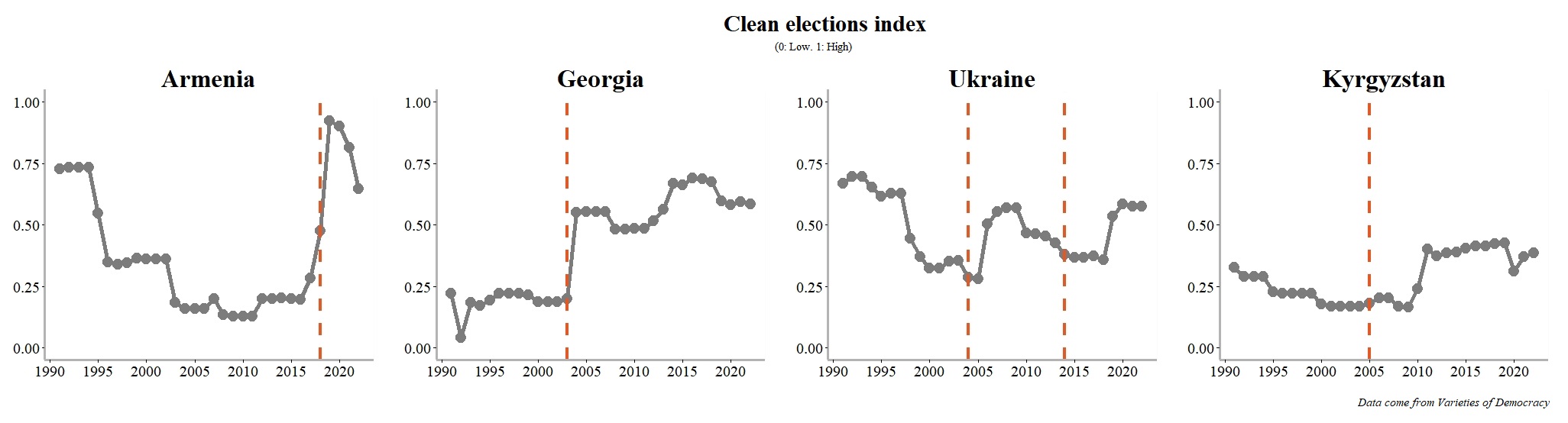

Revolutions also often promise cleaner elections: that is, elections with less registration fraud, systematic irregularities, government intimidation of the opposition, vote buying, and election-related violence. While Ukraine after 2014 and Kyrgyzstan after 2005 did not see such improvements, Georgia and Armenia did gain cleaner elections.

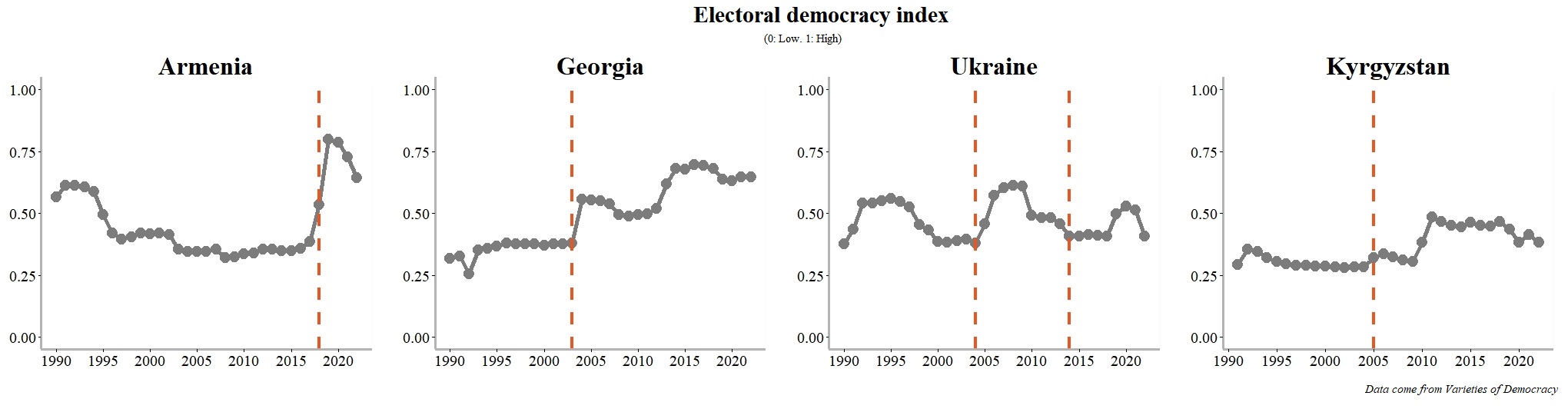

However, the electoral democracy index (a composite index aiming at assessing to what extent a political system satisfies the core value of making rulers responsive to citizens) measured substantial improvements in the post-revolution periods of all four selected four countries, suggesting that political leaders were more responsive to the needs of their population following a revolution.

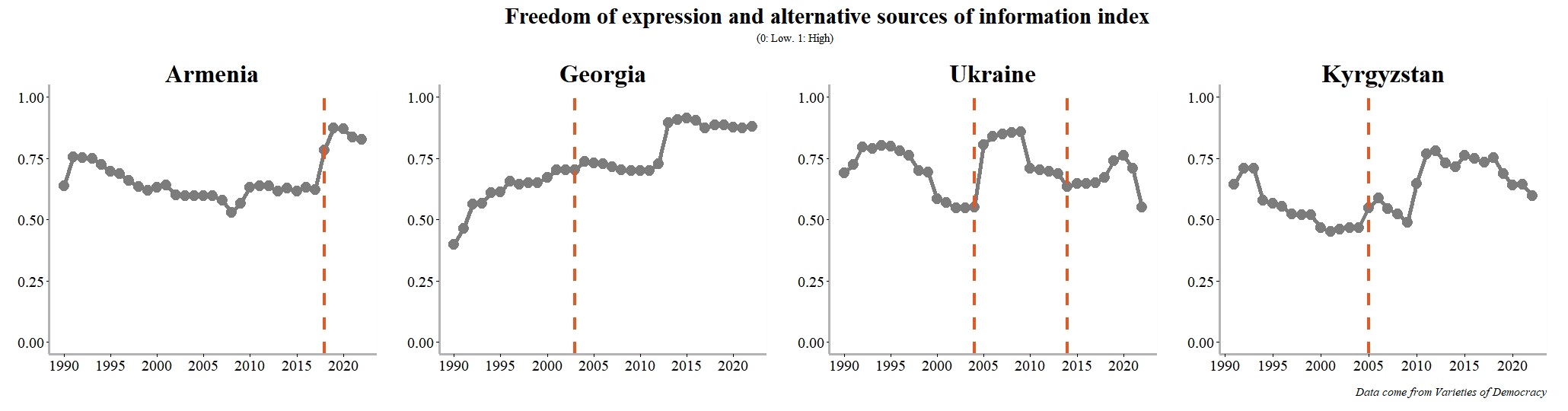

As for freedom of expression and alternative sources of information, post-revolution improvements were seen in all four countries. However, it must be noted that in Georgia, the Rose Revolution did not result in immediate improvements. Georgia’s scores for freedom of expression and alternative sources of information significantly improved only after 2012, when the first peaceful transition of government took place in the country.

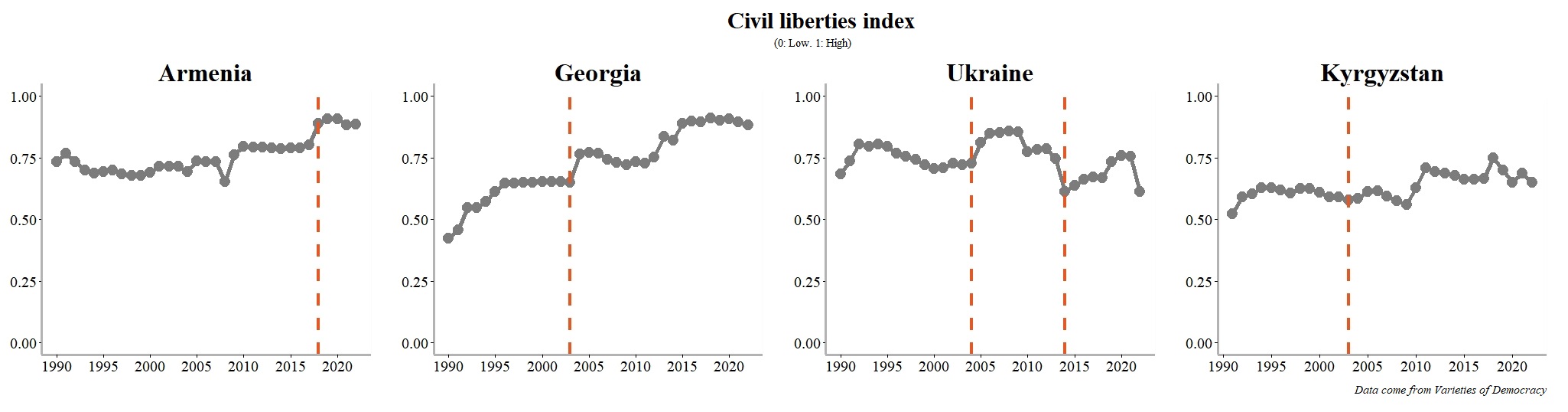

Finally, when it comes to civil liberties, the revolutions in the four countries led to better scores. Civil liberties are understood as the absence of physical violence committed by government agents and the absence of government constraints on private liberties and political liberties.

So what Putin describes as the ‘tragic consequences of colour revolutions’ appear, on closer examination, to be less corrupt state institutions, healthier and more democratic political processes, greater participation of civil society, and better-respected freedoms and liberties; perhaps not so tragic after all.