This disparity in narratives underlines a definitional problem in the political sciences when it comes to conflict resolution, war and peace. The Correlates of War project uses the annual number of casualties to track the duration of wars and conflicts on both an inter- and intrastate level. According to this project, a war is deemed over once the annual death toll drops below 1,000. The problem is that while open armed conflict might cease, a conflict can be far from resolved.

Thus, the conclusion that Georgia’s own territorial disputes can be condensed into five days underestimates the enduring negative impact of the status quo on all sides. Trade and travel are prohibited for inhabitants of Abkhazia and South Ossetia. De-isolation tops Abkhaz policy priorities, while the government in Tbilisi faces the ongoing challenge of settling and providing for internally displaced persons (IDPs).

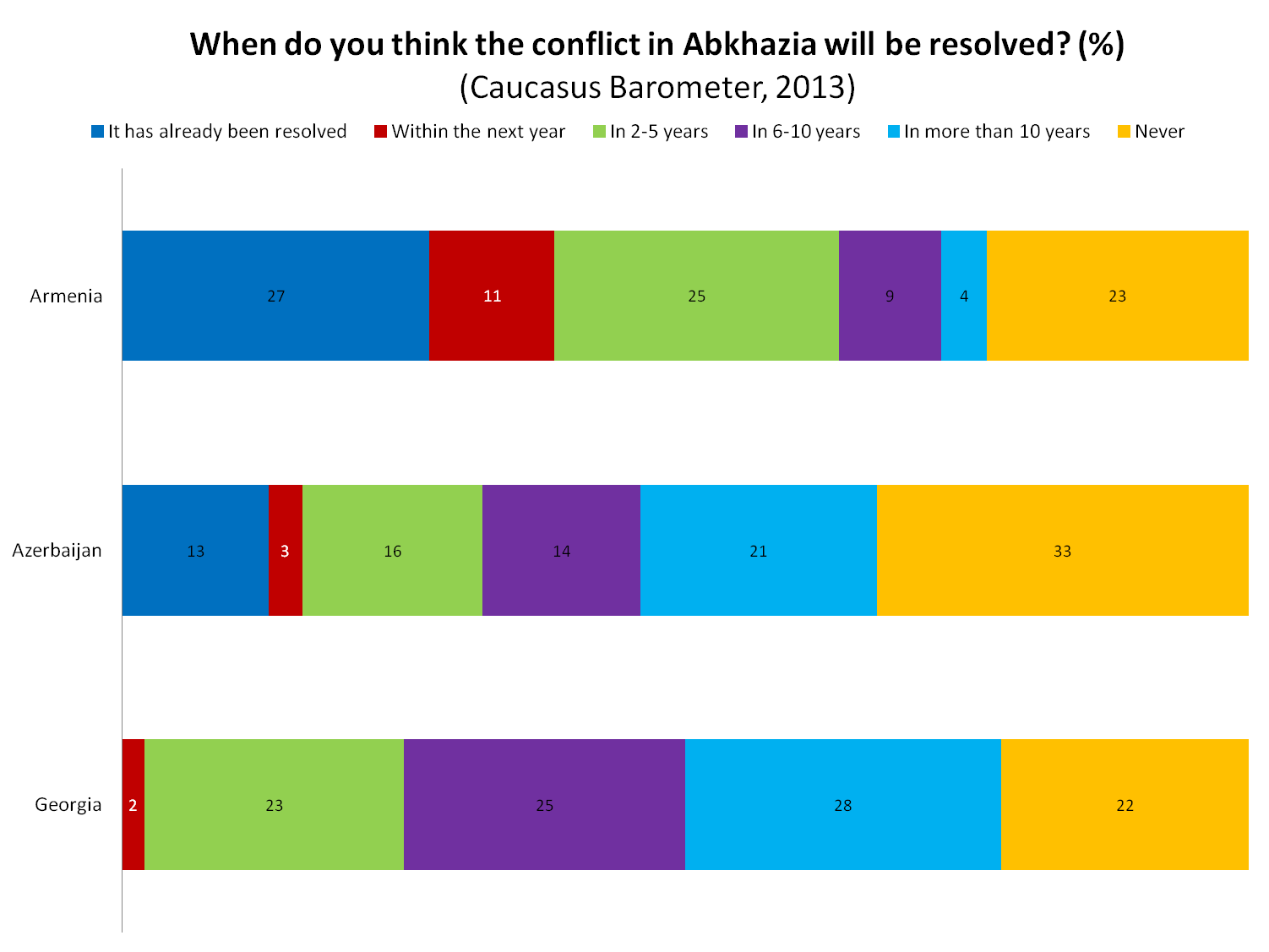

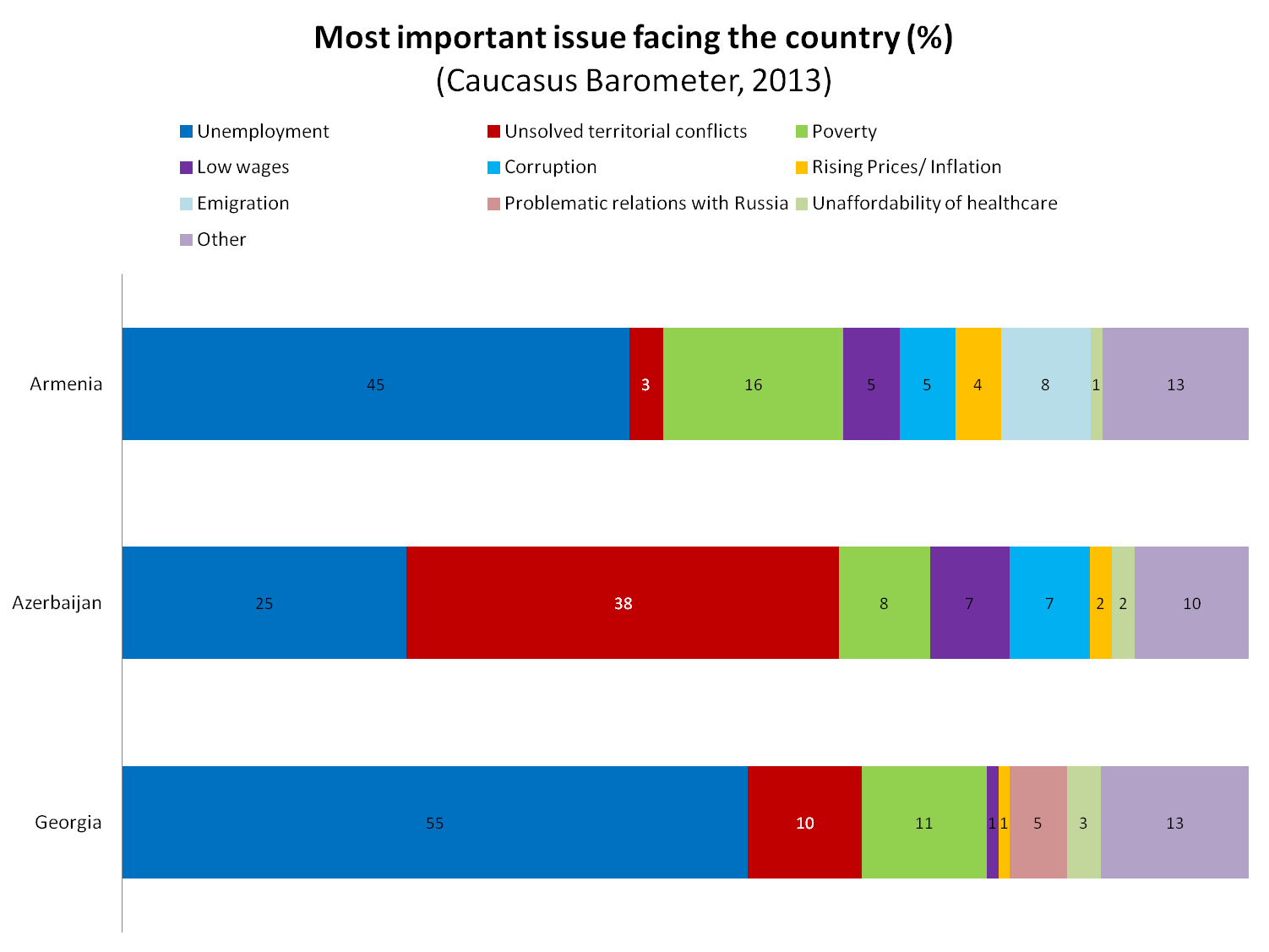

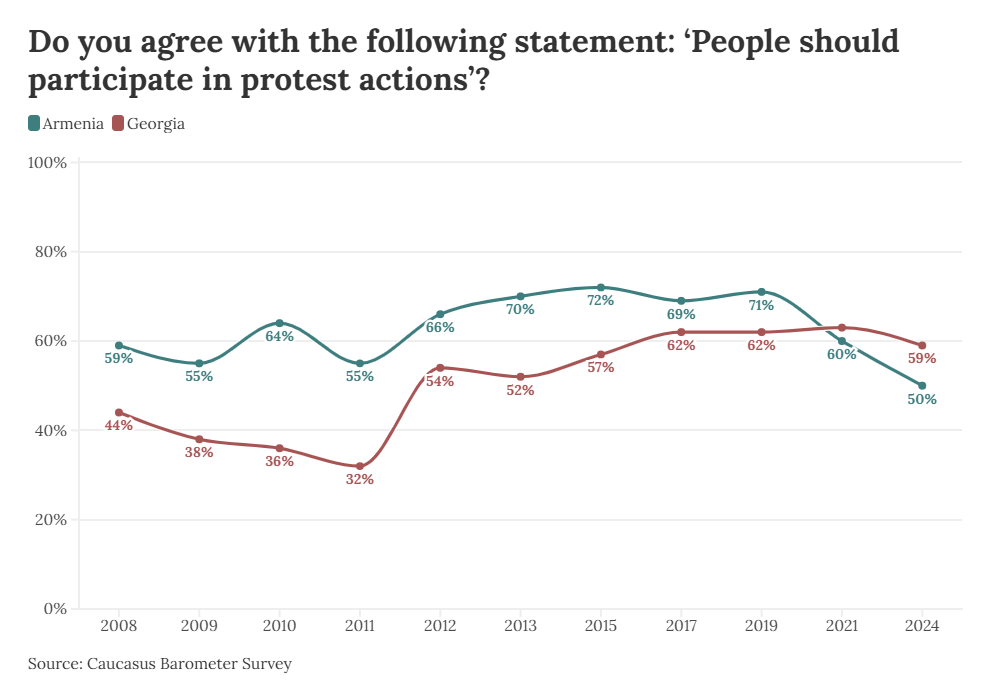

In addition to the Georgia-Abkhazia and Georgia-South Ossetia conflicts, the conflict between Azerbaijan and Armenia over the status of Nagorno-Karabakh is also called ‘frozen’, although experts like Thomas de Waal have suggested that the term ‘simmering’ might be a more appropriate designation. CRRC data is also instructive in this regard. When asked about the top two issues facing their respective countries, 38% of Azerbaijanis named unresolved territorial disputes as the number one problem in Azerbaijan, while 3% of Armenians and 10% of Georgians said the same. The figures in Azerbaijan and Georgia strongly suggest that these issues are not ‘frozen’ (or resolved) in the minds of the local population, although economic concerns also dominate throughout the region.

This blog has shown that national perceptions of conflict can contradict both regional and international narratives. This suggests that our current measures of war and peace are missing an important dimension. The CB provides a starting point for exploring the subject of war narratives. You can find comments about past perceptions of conflict resolution for the Azerbaijani-Armenian case here and for the Georgian case here. You can also access a report on Russian public opinion towards the future of these disputes here. Annual survey data for the South Caucasus region is also available for analysis on the online CB platform.