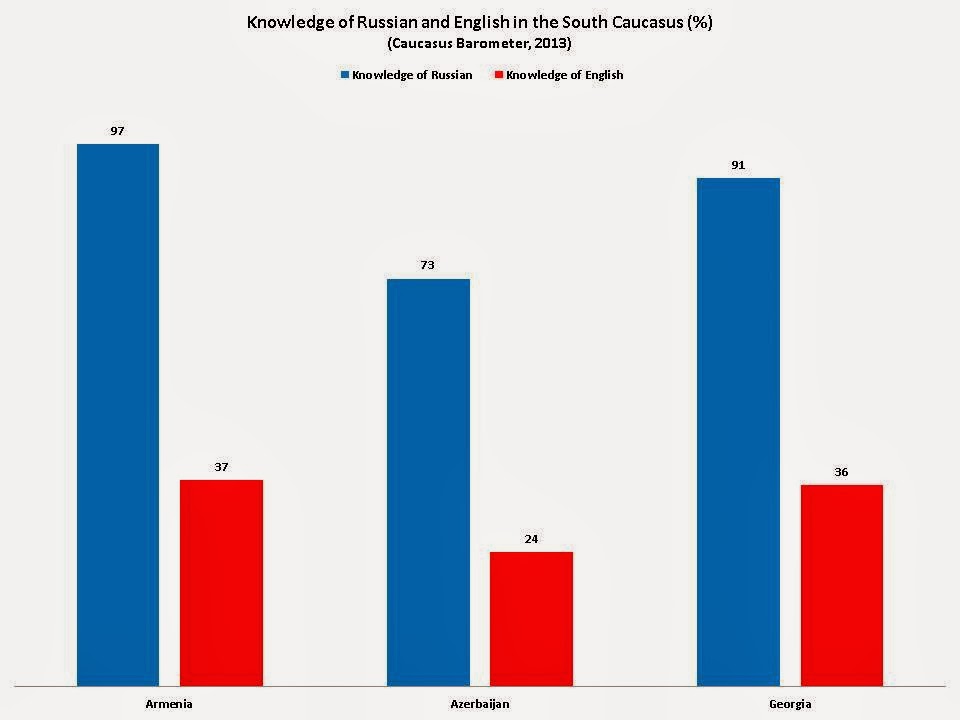

A common language can facilitate business and relationships between people. It can also facilitate the effective management of relations and communication between neighboring countries. Thus, it is important to look at which languages Armenia, Georgia and Azerbaijan share. In the CB, respondents were asked to assess whether their level of English and Russian language was no basic knowledge (1), beginner (2), intermediate (3) or advanced (4). Throughout this blog, “knowledge” of Russian and English refers to people who felt they had at least a beginner’s level of knowledge (i.e. beginner, intermediate or advanced) of the language. The survey shows that at least a quarter of people believe they have some knowledge of English in each country, and a majority say they have knowledge of Russian—especially in Armenia and Georgia.

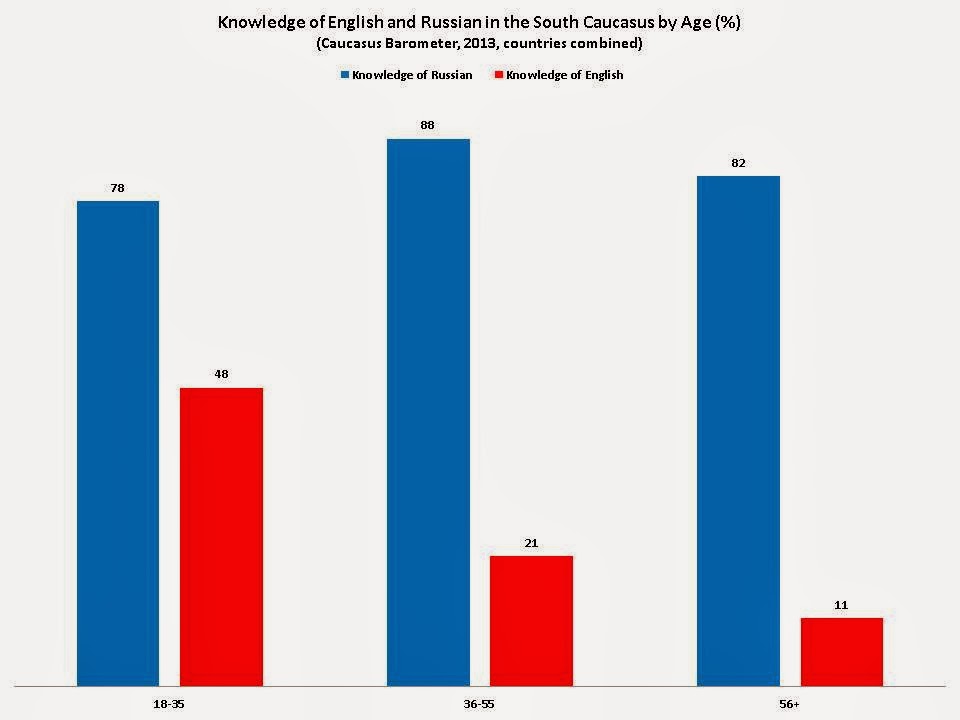

As the graph demonstrates, knowledge of Russian continues to be far more common than English in the South Caucasus, with more than twice as many South Caucasians reporting some knowledge of Russian in all three countries compared to English. Yet, this trend may change as knowledge of English increases, especially among young people. The percentage of 18 to 35 year olds who believe they have at least some knowledge of English is at least twice as high as older age groups in the South Caucasus. Furthermore, knowledge of Russian is lowest in the youngest age group.

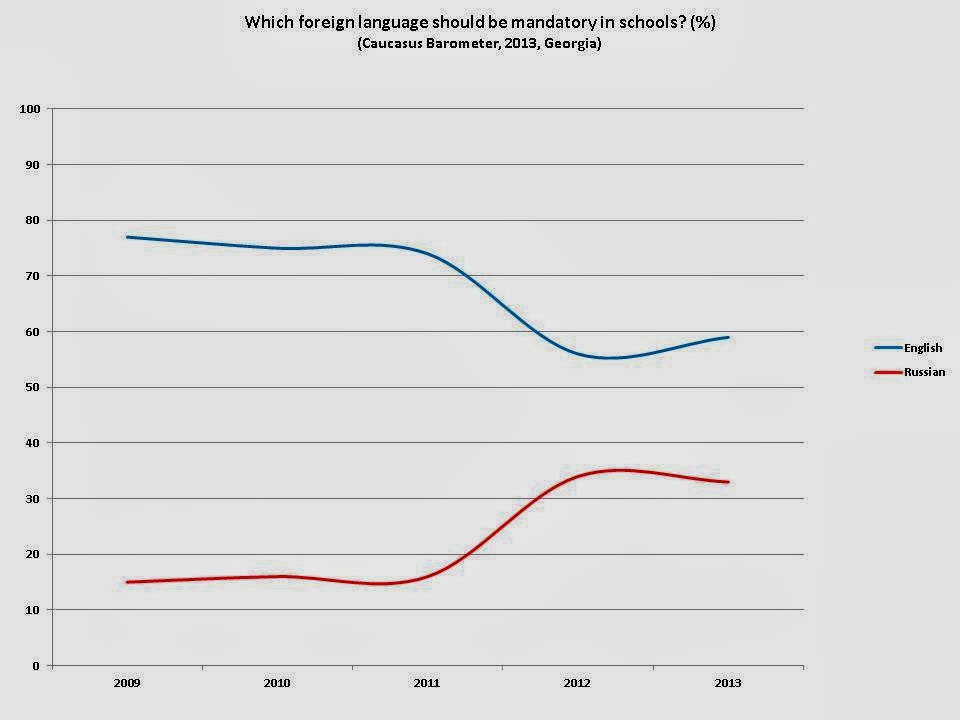

What does the language that Georgians want their children to learn say about how Georgia positions itself internationally? Does it tell us anything about whether or not closer ties with its neighbors are desired? For more information, please visit the following blog post about the Georgian education system and Timothy Blauvelt’s 2013 article on language in Georgia.