Armenia’s announcement in September that it would enter the Eurasian Customs Union led to some dissatisfaction regarding relations with Russia, especially since the announcement came months before the Armenian delegation’s visit to Vilnius to sign a DCFTA (Deep and Comprehensive Free Trade Agreement) with the EU. At the first public debate on the issue in Armenia, organised by the Konrad Adenauer Stiftung and Regional Studies Center, speakers addressed possible attitudes of Azerbaijan and Georgia to the Customs Union. The director of the Caucasus Institute, Dr. Alexander Iskandaryan, noted that Azerbaijan, with its significant energy resources and ability to export them to the EU, does not need to join the organisation for economic development. However, according to him Azerbaijan would not be able to sign a DCFTA given that the country is not a member of the WTO—a prerequisite for all signatories of the document. Georgian Prime Minister Ivanishvili has remained sceptical about the Customs Union, but has not ruled out some form of Georgian participation. While all three South Caucasian countries attempt to diversify their trade (particularly with the EU and Turkey), Russia remains a very important trading partner. Russian firms own critical assets in the Armenian telecommunications, transport, and energy sectors. Data from the Caucasus Barometer (CB) show largely positive attitudes towards conducting business with Russians – not only in Armenia, but in all three countries. In light of the ongoing debate in Armenia on the significance of joining the Customs Union, the CB’s results are worth considering within the wider South Caucasian context.

Armenia has shown the most positive attitudes towards business with Russians from 2009 to 2012, but negative attitudes have slightly increased. The result for 2012 shows an approval rating of 84%, lower than the past four years, yet higher than any result in Azerbaijan during the same time period, and higher than results in Georgia for the prior 3 years.

Azerbaijanis’ approval of doing business with Russians has increased over time, and have shown the biggest change from negative to positive attitudes over the four years shown. The share of those who approve of doing business with Russians has increased from 62% in 2009 to 82% in 2012.

Georgians have continued to have positive attitudes about doing business with Russians over time. Even in 2009, one year after the Russian-Georgian War in 2008, 76% approved doing business with Russians.

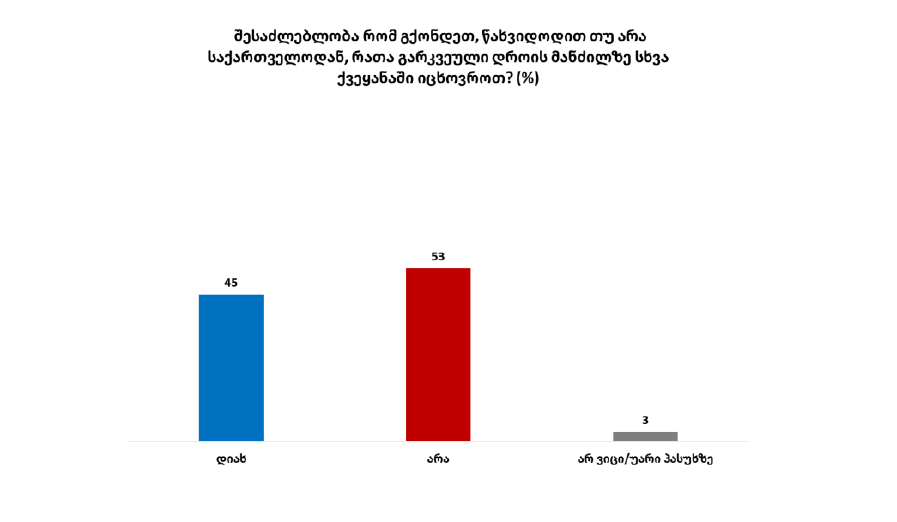

There are several possible reasons for these positive attitudes in addition to intensive trade with Russia and strong social networks with Russians. According to an infographic from the World Bank in 2013, 4 of the top 10 countries receiving remittances by share of GDP are in the CIS (Armenia taking sixth place with 21%). Russia is the top destination for migrant workers across the Former Soviet Union, and it is the destination of choice for 61% of Armenia’s potential emigrants. Considering that the amount of private remittances from Russia to Armenia in the first half of 2013 increased by 113%, Armenians’ positive attitudes may not be surprising. The net amount of remittances sent from Russia to Azerbaijan in 2013 has been 234 million USD thus far, and 263 million USD to Armenia—remittances from abroad were less significant than in Armenia as a share of GDP.During a recent conference in Yerevan on demography, Dr. Alexander Grigorian noted that access to Russia for Armenian migrant labourers could become even easier following Armenia’s accession to the Customs Union, and that this possibly lead to quantitative (higher numbers of migrant labourers) and qualitative (a higher percentage of educated workers) changes in emigration from the country.

What other factors do you think could play a part in attitudes towards doing business with Russians?

If you want to explore these questions in more detail for yourself, we welcome you to download the 2012 and other Caucasus Barometer datasets.