Past wars have taught Georgians both to fear and be tolerant of minorities

Note: This article first appeared on the Caucasus Data Blog, a joint effort of CRRC Georgia and OC Media. It was written by Nino Zubashvili, a researcher at CRRC Georgia. The views presented in the article are the author's alone and do not necessarily represent the views of CRRC Georgia or any related entity.

Since the beginning of the 1990s, Georgia has gone through a number of ethnic conflicts that have not been resolved to this day. Given that Georgia has always been a multi-ethnic country, and the traumatic experience of unresolved conflicts, attitudes towards ethnic minorities matter. Recently released data from the Future of Georgia Survey looks at links between Georgia’s conflicts and the Georgian public’s attitudes towards ethnic minorities.

The data suggests that although the wars have led many in Georgia to see a potential threat of ethnic minorities to the country’s security, people are also conscious of the need for tolerance.

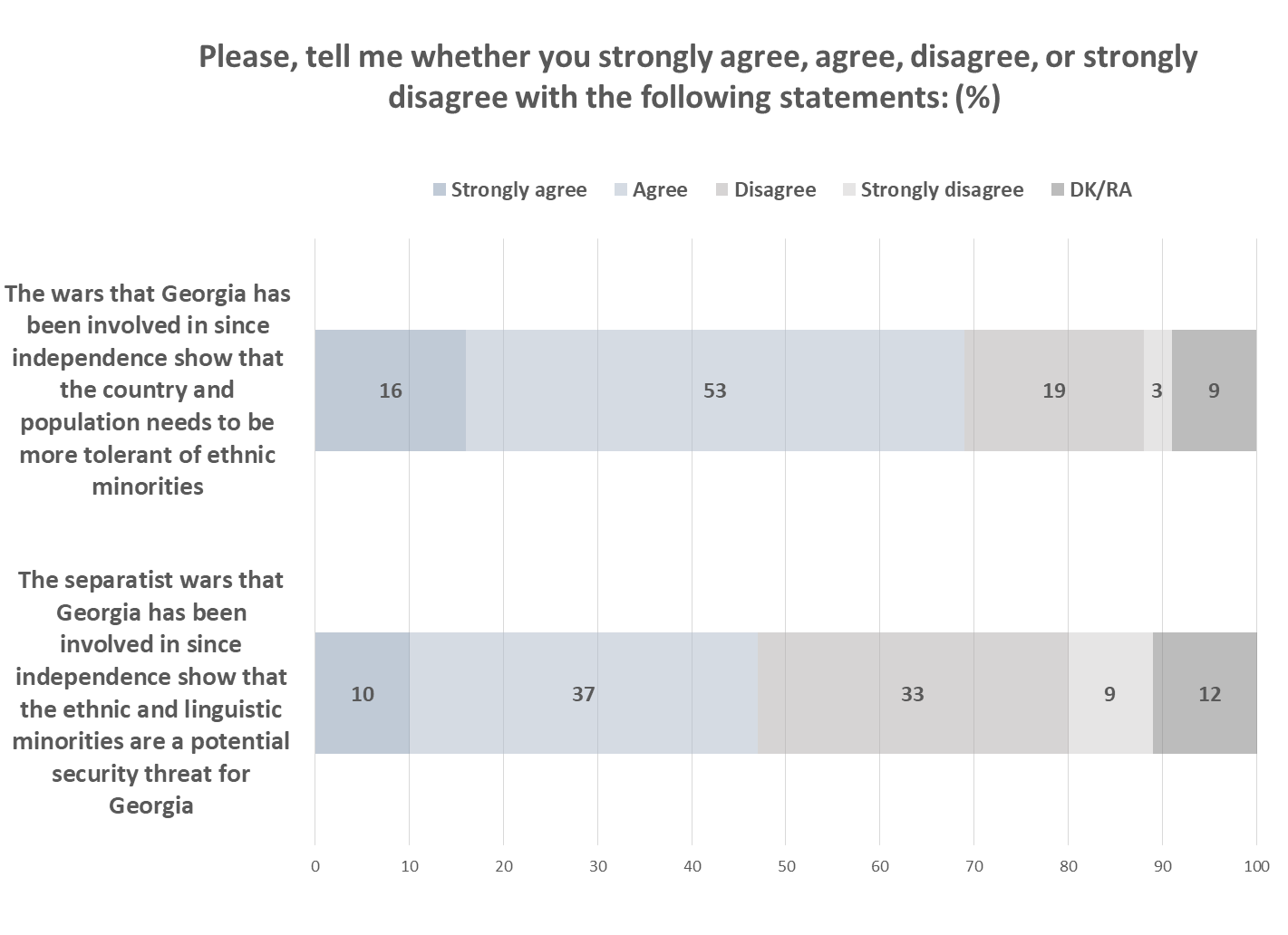

Around half of the public agrees that the wars that Georgia has been involved in since independence show that ethnic and linguistic minorities are a potential security threat for Georgia. But even more, 69%, think that the wars show that the country and population needs to be more tolerant of ethnic minorities.

Thus, these two statements on fear and tolerance are not mutually exclusive, and indeed, 76% of those thinking ethnic and linguistic minorities are a potential threat also see the importance of tolerance. If transposed, 55% of those that see the importance of tolerance, also agree that ethnic and linguistic minorities are a potential security threat for Georgia.

While some studies in pre-and-post-conflict settings argue that ethnic intolerance can be the product rather than a cause of war, the data seemingly suggests past wars in Georgia have shown society that ethnic minorities can be a threat but tolerance can work against that threat. Although needing further research, acceptance of the need for tolerance might be an acknowledgement that ethnic minorities are only a threat if society is intolerant.

Who thinks tolerance matters?

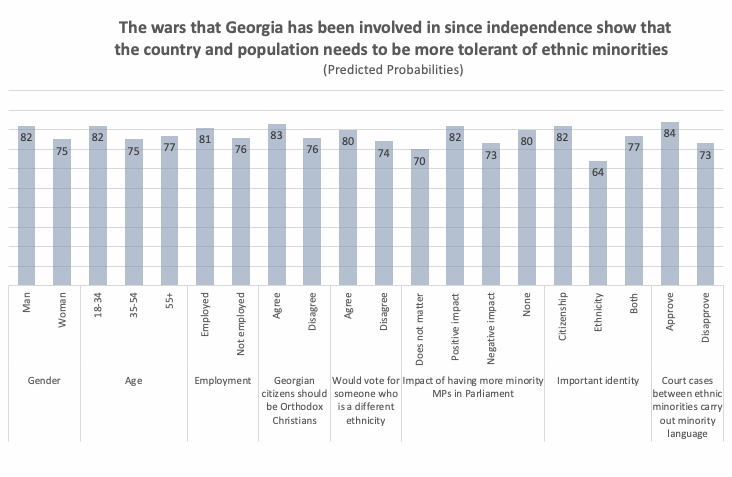

Further analysis suggests that some groups in Georgian society are more likely than others to see the need to be tolerant of ethnic minorities. Controlling for other factors, men are slightly more likely to see the need for tolerance compared to women. So are younger people compared to other age groups, and employed people compared to those not working.

Ethnicity, settlement type, educational attainment, and IDP status are not statistically associated, all else equal.

Those favouring the integration of ethnic minorities into the country’s public and political life are more likely to see the need for tolerance. More specifically, those willing to vote for someone who is a different ethnicity than oneself, those thinking that more ethnic minority MPs in parliament would have a positive rather than negative impact on the country, and those that approve of court cases between ethnic minorities being carried out in minority languages are more likely to see the need for tolerance.

Quite surprisingly, those that think Georgian citizens should be Orthodox Christians are slightly more likely to see the need for tolerance compared to those who disagree.

Social identification seems to be an important factor. Those for whom being a citizen of Georgia is more important than their ethnic identity are 18 percentage points more likely to see the need for tolerance towards ethnic minorities.

Who thinks minorities are a potential threat?

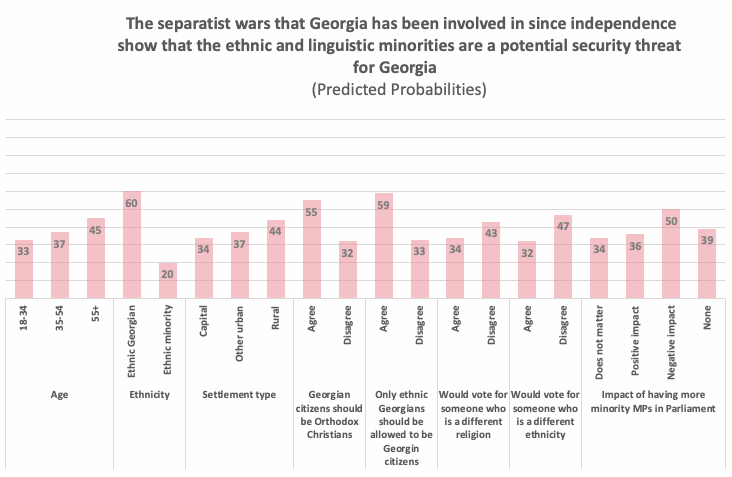

The factors associated with the belief that ethnic and linguistic minorities are a potential security threat for Georgia are largely similar, with several exceptions. Threat perception increases with age.

Ethnic Georgians are three times more likely to see minorities as a potential security threat compared to ethnic minorities. People living in rural areas are ten percentage points more likely to think minorities pose a threat compared to those living in the capital.

Gender, employment status, educational attainment, and being displaced due to previous conflicts in the region are not associated with threat perceptions.

Those thinking that Georgian citizens should be Orthodox Christians are 23 percentage points more likely to see ethnic minorities as a potential threat, and those thinking that only ethnic Georgians should be allowed to be Georgian citizens 26 percentage points more likely.

People willing to vote for someone of a different ethnicity or religion are less likely to see ethnic minorities as a security threat. Those thinking that an increase in the number of ethnic minority MPs would have a negative impact on Georgia are 14 percentage points more likely to see ethnic minorities as a potential threat compared to those thinking that increasing ethnic minority MPs would have a positive impact.

More than half of the Georgian public think that the wars Georgia has gone through show that ethnic and linguistic minorities might be a security threat for Georgia, although even more believe the wars also show a need for tolerance.

Although not self-explanatory in terms of what this says about the Georgian public’s attitudes towards ethnic minorities, these statements are, to a certain extent, associated with ethno-nationalist attitudes.

Identification with one’s ethnic group more than to one’s country is associated with a weaker demand for tolerance. Similarly, those that ascribe ethnicity and religion to citizenship are more likely to view ethnic minorities as a threat. Perspectives on ethnic minorities’ participation in Georgian politics are associated with both perceptions of tolerance and threat.

Note: The data used in the article can be found on CRRC’s online data analysis tool. The analysis of which groups had different attitudes towards the war was carried out using logistic regression. The regression included the following variables in all cases: sex (male or female), age group (18–35, 35–55, 55+), ethnic group (ethnic Georgian or other ethnicity), settlement type (capital, other urban, rural), educational attainment (secondary or lower education, or higher than secondary education), employment situation (working or not), and IDP status (forced to move due to conflicts since 1989 or not). Attitudinal variables tested as part of the analysis included, whether or not one agrees that Georgian citizens should be Orthodox Christians, whether or not one agrees that only ethnic Georgians should be allowed to be Georgian citizens, whether or not one would vote for someone who is different religion than oneself, whether or not one would vote for someone who is different ethnicity than oneself, whether or not one would vote for someone who does not speak Georgian, the impact the increasing number of ethnic minority MPs would have on Georgia (does not matter, positive impact, negative impact, or none), the most important identity (citizenship, ethnicity, or both), whether one approves or not of providing government services in ethnic minority languages as well as Georgian, whether one approves or not of having street signs in minority languages, whether one approves or not of allowing court cases involving civil disputes between ethnic minorities to be carries out in minority languages. These variables were tested independently in separate regression analyses that controlled for the previously mentioned non-attitudinal variables.